Ascend safety expert recognized for contributions to Texas Fire Training Schools

August 05, 2015

Retired Ascend team member Jerry Perkins didn’t just like teaching – he loved teaching.

His expertise was safety. And he never missed an opportunity to share his knowledge at work or in the community, because he believed in the importance of safety.

As safety coordinator at the company’s Chocolate Bayou plant, he led by example. He often reminded his crew, “You don’t have a second chance to get it right. You have to be safe.”

Perkins also taught as a guest instructor at the Texas Fire Training Schools. After training class, he tutored firefighters to help them pass their exams. He often gave them his telephone number and told them to call to let him know if they passed.

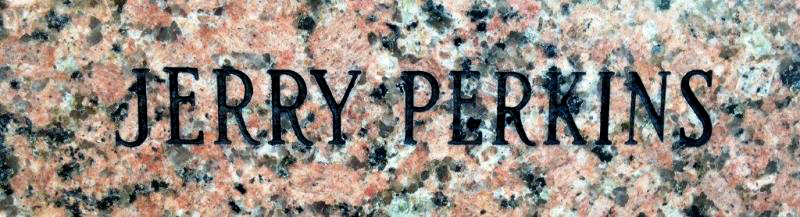

His dedication to safety instruction is now etched in stone. Perkins’ name has been added to the Guest Instructors’ Memorial at Brayton Firemen Training Field in College Station. His family, friends and Chocolate Bayou team members attended the induction ceremony on July 15.

The memorial honors individuals who made significant contribution to the Fire Service of Texas through the training programs of the annual Texas Fire Training Schools. Honorees must be deceased and have at least 10 years of teaching experience with the training schools.

Perkins taught as a guest instructor at the Industrial Fire School for 23 years and worked at Chocolate Bayou for 34 years, before retiring from Ascend in 2005. He was a plant processor and then a safety coordinator. In retirement, he taught first aid, CPR and hazardous waste operation and emergency response classes at numerous companies in Texas and Louisiana. He died on April 1 at age 64.

Perkins taught as a guest instructor at the Industrial Fire School for 23 years and worked at Chocolate Bayou for 34 years, before retiring from Ascend in 2005. He was a plant processor and then a safety coordinator. In retirement, he taught first aid, CPR and hazardous waste operation and emergency response classes at numerous companies in Texas and Louisiana. He died on April 1 at age 64.

“Jerry was an inspiration and mentor to hundreds of students and fellow instructors, demonstrating his dedication and passion for the fire school, fire safety and, most importantly, his life values,” said Don Hale, a friend and an instructor at the fire schools. “Through the memorial wall, the legacy of Jerry Perkins lives on in each of those whose lives he touched.”

Perkins worked and taught with some of the world’s best fire instructors at the training schools. In 2005, he was promoted from lead instructor to the new position of section leader to teach an advanced exterior course, which all instructors were required to take. He excelled in the course and was already teaching most of the course material, Hale said.

In addition to teaching, he helped students with other courses through his tutoring sessions. He rented space for the sessions, made flash cards and quizzed students on their knowledge of firefighting skills.

The tutoring sessions soon grew from 15 students in the first year to as many as 80 students the next year. He went from using flash cards to using a power point presentation.

“Jerry was committed to the success of every student,” Hale said.

When the Industrial Fire School leadership team heard about Perkins’ study hall, they encouraged students to attend. The training school also saw test scores increase substantially, Hale said.

Today, 90 percent of all interior and exterior advanced class students attend the study hall, he said.

Perkins also cared about his Chocolate Bayou team members. Every year he took his shift emergency response team to the Industrial Fire School for training. And every year he and the team took a picture in front of the memorial wall, said shift team member Matt Brown. Perkins appreciated that the schools honored instructors and, in his honor, the team has continued the tradition of taking a picture, he said.

“Jerry was my mentor. He went the extra mile to get to know his fire crew and even the operators and engineers,” Brown said. “But his biggest thing was to stress the importance of safety, and he expected a lot from his people.”

Team member Robert Hasse recalled how Perkins took the time to work with his daughter Abby. She had a middle school project about fire extinguishers and which to use on which type of fire, and he taught her the different uses.

“They even lit a fire in his backyard so she could put one out with an extinguisher,” Hasse said. “He got the biggest kick out of stuff like that.

“He taught me how it important it was to pass on information to others, to lead by example, and include others in the process in order to build an effective team,” he said.

Perkins’ son James, a processor, and his niece, Roxann Weigel, an environmental technician, both work at Chocolate Bayou. Weigel said she enjoys teaching and training because of her uncle’s work.

“He was always looking for opportunities to serve others,” Weigel said. “He was just the most amazing man you could ever hope to know.”

Thank you for your interest in Ascend Performance Materials

Page Title: Ascend safety expert recognized for contributions to Texas Fire Training Schools

Page URL: https://www.ascendmaterials.com/news/ascend-safety-expert-recognized-for-contributions-to-texas-fire-training/

Americas: NorthAmericaCustomerService@Ascendmaterials.com

Asia / Pacific / Australia: AsiaCustomerService@Ascendmaterials.com

Europe / Africa: EuropeCustomerService@Ascendmaterials.com

Sales & Product Inquiries

Ascend Performance Materials SPRL

Watson & Crick Hill Park

Rue Granbonpré 11 – Bâtiment H

B-1435 Mont-Saint-Guibert, Belgium

Phone: +32 10 608 600

Product & Expert Support

Ascend Performance Materials (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Unit 3602, Raffles City Office Towers

268 Xi Zang Road (M)

Shanghai 200001, China

Phone: +86 21 6340 3300

©2024 Ascend Performance Materials